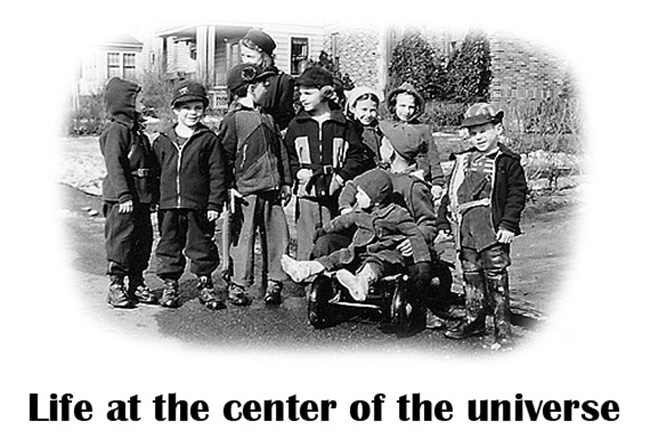

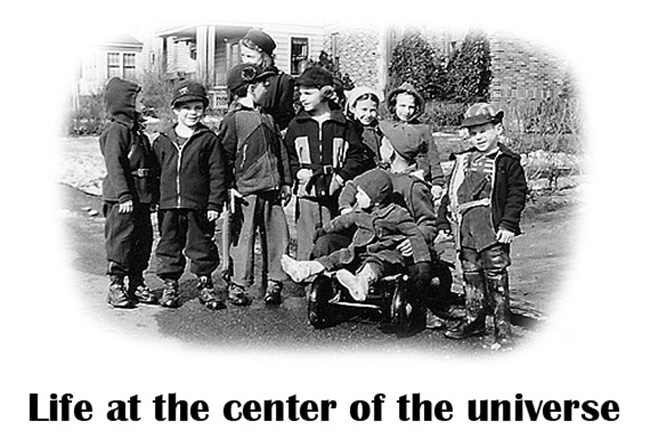

In the late 1940s and early '50s, the center of the universe was a one-block, dead-end street in Solvay, NY. You didn't have to live on Russet Lane to feel the same way, especially if you were a boy who enjoyed sports. There were better facilities in a park just a short walk away, but we played our games in the street, in driveways and our yards. I grew up thinking I loved these games, but later discovered that what I really loved was the way we played them on Russet Lane. Each game had its own peculiarity, its own special challenge.

Touch football was played in the street and on an incline along a 100-foot stretch between two utility poles and occasionally around parked cars. However, the most interesting challenge was presented by the branches overhead in a tall elm tree and the spreading maple across the street. When punting or kicking off (which we did by passing the ball), you had to throw it between those branches. If not, the ball came straight down or, worse, landed behind you, perhaps resulting in a safety (which we mistakenly called a touchback). Only in a Russet Lane football game was it possible to kick off and find yourself behind, 2-0.

DRIVEWAY BASKETBALL began in 1943 in the Smolinski driveway. Bill Smolinski made a wooden backboard, my welder father Buster Major made the rim, which would prove to be the biggest challenge. My father had used a basketball as his measuring stick. He never measured a regulation rim, which was much larger than the one that went up on Bill Smolinski's backboard.

The driveway was a few feet wider than the two-car garage. A five-on-five game was possible, but even four-on-four was crowded. The most interesting hazard was the drop-off from a retaining wall that separated the Smolinski driveway from our backyard. That drop-off increased from about 12 inches to 30, depending on your distance from the garage. Some players used it to their advantage, none more so than John "Bombsight" Savo (later a Solvay mailman), who perfected a running, fadeaway jump shot. That is, he'd jump, shoot and fade about 8 feet into our yard. Few defenders followed him over the wall.

The small rim probably contributed to the longest winning streak in Solvay High School history. Every member of the team, captained by Bimby Smolinski, had played in the Smolinski driveway. I don't know how long the streak lasted; I do have a Syracuse Herald-American clipping, a photo of the team the day before they were going for their 27th straight. Many years later, one of the team members, Joe Cristoforetti, joked to Bimby that his favorite basketball moment was when he finally made a shot in the Smolinski basket.

Years later Syracuse Nationals great Dolph Schayes touted a small rim he placed inside a regulation rim. By using it, he said, players could improve shooting accuracy. That was old news to Solvay teams of the late '40s.

By the 1950s we moved up the street to the Mathews backyard, playing on a regulation rim. Sometimes we played across the street and up a slight hill in the Mazzochi driveway. On a few occasions we even tried playing full court, from the Mazzochi basket to the Mathews basket, a distance that was nearly twice as long as a regulation court. Needless the say, these games never caught on.

OUR FAVORITE sports venue was a miniature softball field in a sunken, 75-foot-by-75-foot space behind the Mathews garage. All you needed were four players per team. There were no outfielders because the center field fence was just behind second base. A ball hit over that fence was an out (though eventually we allowed a home run if you cleared the top of the poplar trees in center field). It was always best to keep the ball on the ground. Jimmy Mathews was especially good at hitting grounders through a small hole in the fence. He cleared the bases almost every time.

On summer evenings we played Tin Can Copper (elsewhere known as Kick the Can). Of all my childhood memories, it’s Tin Can Copper and another street game, Jailbreak, that say the most about how neighborhood life has changed over the years. There we were – five, six, seven of us, sometimes more – running, hiding and occasionally screaming from yard to yard after dark, often lurking under a neighbor's window, hiding from whoever was “It” and waiting for an opportunity to race “home” (the telephone pole in front of Ronald Blair’s house). I can’t imagine anyone today tolerating the noise, the property invasion or the dangerous tree-climbing that went on in the Blair maple where kids disappeared among the leaves, about 25 feet off the ground.

Not that Mr. Blair always tolerated the nonsense. One night he charged out and yelled at a shadowy figure swaying high up in the tree.

"Get down, Red Mathews, or I'll call your father!"

"Go ahead!" challenged the boy.

Mr. Blair went into his house and made the call. And Joey Pozzi left his hiding place, laughing all the way home. |

| |

| A Russet Lane Top 10 (Plus 1) |

10. Halloween 10. Halloween

On Russet Lane, Halloween was a two-night affair, sometimes three, which wasn't a bad idea for adults who went overboard in buying candy and would rather give it away than give in to temptation. You could expect children at your front door on Oct. 30, that's how anxious we were.

And none of this mamby-pamby "Trick or treat?" business. Our approach was direct and demanding: "Hotchee botchee, give me something to eat!"

In those days we didn't suspect neighbors might try to maim or poison us; we gladly accepted apples and homemade treats, the favorite being Mrs. Wylie's popcorn balls. We went back for seconds on Nov. 1.

|

|

9. Snowforts

Syracuse is notorious for its winters. Only an odd duck would move to Central New York for its weather. But we enjoyed the snow, especially school-closing blizzards that provided building material for snowforts.

And, yes, as children who grew up during World War II, we built snowforts, not snowhouses. We were at war with an invisible enemy, though occasionally we'd divide into rival armies for snowball fights, but we had much more fun building something together.

Most memorable was a blizzard in the late 1940s that deposited a huge drift in the Bagozzi back yard, snow so deep that when we carved it out, most of us could stand up in the cave-like room we created. We then tunneled a la The Great Escape to the end of the drift, making a smaller chamber along the way.

When we weren't making snowforts, we'd be sledding from the end of Russet Lane down to Woods Road Park. Little did we know that when we became grownups we'd eventually curse the weather we had loved as children.

|

|

8. The hill

The north side of Russet Lane backs up against a hill then owned by the Solvay Process Company. Almost anyone could use the hill – for almost any purpose. During the 1940s there were several Victory Gardens tended by various neighbors and families from nearby Orchard Road. There also was the infamous Ci-Yi's shack, a tool shed we imagined was the home of the bogeyman.

Along the eastern edge of the path was a nature walk – though, no, we didn't call it that – bordered by a variety of small trees, bushes and wildflowers we weren't old enough to appreciate. This was the most interesting route from Russet Lane to "downtown" Solvay, about four blocks away.

The hill overlooked the Solvay Process factories and its unusual lifeline, the limestone pile, itself a vivid hometown memory. Past the Process was Onondaga Lake. To the east was downtown Syracuse. Along one ridge of the hill we flew paper model airplanes (ordered through radio's Jack Armstrong Show) competing to see whose would sail the farthest.

Occasionally we camped overnight on the hill, but never, of course, in mid-August when the hill was filled with fireworks fired during the Feast of the Assumption Field Days at Woods Road Park. (See #3, below.)

The hill also was the dividing line between East and West Solvay, and for awhile in the mid-1940s the sight of a young West Solvayite on the hill triggered an alarm that summoned Russet Lane boys to Joey Pozzi's backyard at the end of the street, ready to defend their East Solvay turf.

Detente was established by 1950 when Russet Lane was the village's sports center, drawing kids from all corners of Solvay to the Smolinski driveway to play basketball.

The hill remains largely undeveloped, but it is now private property, sold by a company for which Solvay was named, but a company that deserted the village many years ago. |

|

7. Blair's rock

Gerald Blair, who lived next door to us at 102 Russet Lane, was a lawn fanatic. He had the greenest, grassiest, prettiest lawn on the street. At the edge of his property, separating his lawn from our driveway, was a bowling-ball-shaped hunk of rock that was annually given a coat of white paint. Whether it was decorative or intended to force all traffic into our driveway away from Blair's grass was uncertain, though I suspect its purpose was the latter.

No matter, the rock became a Russet Lane landmark, respected even by those who were amused by it. That changed about 1960 when Blair, Solvay's Democratic Party chairman, had a falling-out with Buster Major, Solvay's Democratic mayor. Blair expected Major to step down after his fifth term in office; Buster chose to run for re-election.

Relations between the two neighbors worsened when Buster's daughter Mary began dating a boy who insisted on backing into her driveway. One night he backed over the rock and tore up some of Blair's lawn. A few days later a wire fence went up on the Blair property, inches from the Major driveway. When snow arrived, the Blairs took to summoning police if a Major was seen shoveling the white stuff against their fence.

Relations between the two families was strained and silly, especially after a blizzard when there simply wasn't room for all the snow to be dumped on the narrow strip of land on the Major side of our driveway. (While clearing the driveway I'd fling an occasional shovelful over the fence toward Blair's house, awaiting a reprimand.)

All the while the rock remained in place, next to the end of our driveway. Until the night I cracked. I've kept this secret nearly 50 years, but now I'll confess to one of Solvay's unsolved crimes, an act of vandalism that left a brown hole in Blair's green lawn.

I sneaked out one night about 2 a.m., put the rock in my car, and drove it five miles or so and tossed it into Geddes Brook.

My father lost that election, by the way, and things remained chilly between the Majors and Blairs until after Buster and Gerald died. Then Helen Major and Gertrude Blair, widows with a lot in common, became friends again.

I wonder if Mrs. Blair ever asked my mother about the rock. |

|

6. Major's garage

Our garage existed before our house, which was built in the early 1930s. What our garage was for sure, I don't know. I was told it was a small stable and/or a carriage house. Whatever, it was unusual, with two huge front doors that slid horizontally – but didn't slide easily. My father's early cars, including the 1937 Dodge he had for the first 13 years of my life, fit inside a closed garage. The automobiles that followed, starting with a 1951 Pontiac, were slightly too long. We parked at an angle that allowed us to slide a door along the rear bumper almost to the end. There was no locking this garage.

Frankie Bagozzi and I once set up chairs inside the garage and charged admission (a nickel) when my father borrowed a 16 mm movie projector and rented some films, one starring The Three Stooges. (We made 65 cents.)

The garage also was the site of the classic 10-round (or so) fight between Jimmy Mathews and myself, using the boxing gloves that had been a Christmas present. Mathews, now a Catholic priest, won by TKO in round 10, taking every round along the way.

It was used as a clubhouse, first by me and Frankie, later by my sister Mary Beth and her friends. Frankie and I used the garage attic, Mary usually conducted her meetings on the first floor. Mary's clubs didn't last long. As soon as someone else was elected president she'd disband the club and start another one. She painted the name of one of her clubs – I believe it was the Solvay Sub-Teen Club – on the inside of one of the garage doors. That sign may still be there – if the garage is still standing, that is. I stopped on Russet Lane a few years ago to look at the house. The garage was leaning precariously to the right. It looked like a stiff breeze could knock it down. |

|

|

5. The jit

I'm guessing at the spelling, assuming it was short for jitney. The jit (photo, below) was unique to Russet Lane. At least, it seemed to be. It belonged to the Smolinski family, though my cousins seem a bit vague on the jit's history. Today the whereabout of the jit is a mystery. Somewhere, someone may be riding a treasured piece of our past.

The jit was a narrow, four-wheel toy shaped in front like an old, Indy-style racer, complete with steering wheel. It functioned like a soap box derby car. You'd start at the top of Russet Lane, pump a few times with your good leg, then ride the rest of the way.

The problem was making a turn. The vehicle was too long and narrow to negotiate most turns, and since the jit belonged to the Smolinskis, most riders attempted to turn into the Smolinski driveway which rose up an incline about three feet and was separated from our front yard by a concrete retaining wall. Result: drivers who managed to avoid flipping the jit wound up sailing off the retaining wall. Riding the jit was one of the original X Games.

It was an impractical toy, but unique. That, along with its unusual name, made it irresistible. It was so well remembered that it was mentioned by Father Jimmy Mathews during the eulogy at Gertrude Smolinski's funeral. And I expect, as Charles Foster Kane did with Rosebud, at least one Smolinski, for his final words, will utter "The jit!" |

|

|

4. Mathews camp

The Russet Lane rite of passage for boys was being invited to Mathews Camp on Otisco Lake. Attorney Daniel Mathews and his wife had three children – Peggy, Daniel Jr. (better known as Red) and Jimmy. They'd pack an incredible number of kids into their station wagon for the 45-minute drive to the lake and a cottage that was located at the end of a long, dirt road past a Boy Scout camp.

There was an interesting age range among the boys, from about 10 to 17 years, something that worried my mother when I was asked along for the first time. She said no, which led to my most memorable tantrum (which should have been evidence enough that my mother was correct), but the intensity of my feelings wore down her resistance (and probably gave her a headache that only my absence could cure).

Anyway, I went and continued to go for several years. Otisco was a good swimming lake because ... well, you had to swim. The lake's rocky, often painful bottom prompted you to stay afloat.

The Mathews had an interesting World War II raft large enough to seat about a dozen kids. The water-filled, net-lined opening inside the raft was like a small pool, about three feet deep above a wooden bottom. But the swimming was done outside the raft in water 6-to-8 feet deep.

We behaved like the Dead End Kids, but I don't recall any mishaps. It was an example of how peer pressure can be a good thing, forcing you to overcome fears to accomplish something you might not otherwise attempt. Like diving off the Mathews dock.

Of course, no amount of peer pressure can get you to dive again immediately after a stinging bellyflopper, which, unfortunately, was my specialty. |

|

3. August 15 field days

In the Catholic Church, August 15 is the Feast of the Assumption, honoring the Virgin Mary's angel-assisted assumption into heaven. Solvay's Catholic Church, St. Cecilia's, celebrates the Assumption with a three-day fair at Wood Road Park at the end of Russet Lane. The event was incredibly popular throughout the area, drawing thousands of people  from nearby communities for midway rides, games, food and, most importantly, a terrific fireworks demonstration at the end of each evening, with the biggest and best reserved for the final night, August 15. from nearby communities for midway rides, games, food and, most importantly, a terrific fireworks demonstration at the end of each evening, with the biggest and best reserved for the final night, August 15.

Russet Lane residents felt special. We could walk to the fun while others scrambled to find parking spots. If you had been out and were driving to your home, you'd be stopped by a policeman and told you couldn't enter – until you said the magic words, "I live on Russet Lane." It was your VIP pass.

Some residents were lukewarm about the fireworks; they were house-shakingly loud and, I guess, potentially dangerous, rockets that had just entertained the crowd remained ember-orange as they fell and drifted toward houses on the north side of the street. For some of us that was part of the show. I don't recall any fires – well, any serious fires.

My two favorite August 15 memories:

1. Father Carl Denti probably was the most popular priest in St. Cecilia's history, an engaging man not afraid to go for a laugh during a sermon or out in public. Fireworks weren't restricted to the evening show. One was fired after each of the two Aug. 15 morning masses. I went to the 8:15 mass one year and as Father Denti came out of the front door afterward he was greeted by a tremendous boom. Without missing a beat he put his hands on his chest and comically staggered down the church steps.

2. The 1950s was the heyday of the Cold War between the United States and the USSR. In preparation for an atomic bomb we all prayed would never be dropped, people throughout the United States were told to duck and cover. We had duck and cover drills in school.

Okay, so now it's the August 15 before my sophomore year in high school and I'm sound asleep about 7:45 a.m.

BOOM!! I'm suddenly awake, but momentarily unaware what day it is. But I've been well trained. I dive out of bed toward a corner and assume the duck and cover position. And I lived to talk about it. |

|

2. Street games

A gang of young kids running through your yard, some of them hiding under your living room windows. More running, a loud shout, "Got you, Frankie! You're up in the tree!" Seconds later another shout, "Olley olley in free!" Another thundering herd, the sound of a tin can hitting pavement, and your yard is invaded once again.

I can't imagine the scene ever being repeated. More's the pity. |

|

1. Street sports

The last time I saw a group of pre-teen boys attempt to play touch football in the street, the game ended after one play. Two of the boys got into an argument over pass interference.

I actually saw a pick-up basketball game end in a fight when a young man claimed goal-tending against someone who could barely jump high enough to touch the bottom of the net.

There are a lot of people these days who don't know how to play unsupervised sports. They don't know what they're missing.

Count me among those who believe organized sports for kids – leagues that place kids in an environment that includes an army of coaches and officials, cheering and trash-talking parents, electric scoreboards and facilities formerly denied anyone short of a professional athlete - have not only removed most of the game's fun, but also the initiative, ingenuity and independence fostered by sandlot and street sports.

And don't get me started on those people who encourage children to participate in games where no one keeps score . . . But enough. On Russet Lane we found ways to play football, softball and basketball without ever leaving the street, a backyard or driveway. We won, we lost and we had a great time. |

|

Do you hear what I hear?

One Russet Lane memory that was not among my favorites was revived by an e-mail from a former neighbor, Dolores Bagozzi Evans, who had a much greater appreciation of what, for me, was an annual ordeal. For details, see Sleepless in Solvay. |

|

|

10. Halloween

10. Halloween

from nearby communities for midway rides, games, food and, most importantly, a terrific fireworks demonstration at the end of each evening, with the biggest and best reserved for the final night, August 15.

from nearby communities for midway rides, games, food and, most importantly, a terrific fireworks demonstration at the end of each evening, with the biggest and best reserved for the final night, August 15.