| HOME • FAMILY • YESTERDAY • SOLVAY • STARSTRUCK • MIXED BAG |

|

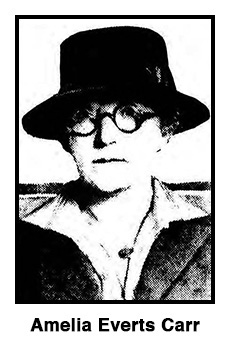

She used several aliases, and when she last attracted attention, in 1950, she was using the name Amelia Everts Carr. But when she first came to my attention, while reading newspapers from 1921, she was identified at Mrs. Mildred M. Boniface. |

||

|

||

There were witnesses when Mary Mountford jumped from the ferryboat on Janaury 15. That led police to conclude a woman drowned in the Delaware River that night, but she would remain unidentified until her body surfaced several weeks later. As for "the Harjes estate" mentioned in the New York Times story, that is a reference to John H. Harjes, a partner of J. P. Morgan. Harjes died in 1914; I have found no mention about any complications with his estate. His position at the J. P. Morgan firm was taken by his son Henry Herman Harjes, who died in a polo accident in 1926. However, since Harjes lived mostly in Paris, it was relatively easy for a con artist to claim a family relationship. Mildred Everts would claim the story about her relationship with a wealthy member of the J. P. Morgan firm was one she had heard as a child from her mother who claimed the family would someday be very rich. For 50 years, the con woman said she was the granddaughter of John H. Harjes, then changed her story slightly, saying she was the daughter of Henry Herman Harjes. It was one of her favorite cons, and she had little trouble finding trusting marks. She took her act on the road for several years. A New York Post article (January 12, 1942) by Maureen McKernan said there were charges against the con woman pending in Maryland, Texas, Colorado, Utah, Oregon and Washington, and police in nine other states wanted to question her. However, by the time this article appeared, she was back in New Jersey, where she was living comfortably in Newark as Mrs. J. Clarence Carr, wife of a real estate broker and member of Roseville Methodist Church, until another parishioner accused her of defrauding her of $4,700. According to Ms. McKernan's story, prosecutor William Wachenfeld said the Mrs. Carr had bilked fellow church members of about $100,000. The Rev. Edson Leach, pastor of the church, was stunned, saying Mrs. Carr "was always doing something for somebody —picking up an old lady at the church door to take her home, or sending her car for children to bring to Sunday school. She was charming and gracious, always smiling." Mr. Carr said his wife had "been a queen to me. She was noble, good and loyal." And Newark police tended to shrug off the accusation against Mrs. Carr, until they investigated the woman's background. They discovered the woman was first arrested in 1891, when she was 15, on a fraud charge. She served her first time 10 years later, 10 months in Trenton jail for obtaining money under false pretenses. She had served prison terms in Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Walla Walla and Spokane, Wash., and San Quentin, Cal., and had used eight known aliases and had been arrested 19 times. While on the West Coast, she joined Jehovah's Witnesses, and went to Newark as a delegate to a conference. In Newark, she met a woman who had been employed by Carr as a maid to his first wife. The woman introduced her to Carr, and they soon married. According to Ms. McKernan's story, Mrs. Carr told her husband the old story that she was related to a partner of J. P. Morgan, but she refused her husband's request to meet her family, saying her relatives were "crass people, interested only in making money." Meanwhile, she began conning members of Roseville Methodist Church where her husband was considered one of the leaders. She sometimes claimed she would soon receive a large inheritance, but meanwhile was in need of money. Other times she said was looking for investers to help her develop her oil lands in California. Or she would talk people into letting her invest their money for them. She used the money for jewels and a car and chauffeur, but at the same time appeared to be generous, at least with her time. No contracts were ever written, because, she said, "There is no need for anything in writing between two good Christians." As news of her arrest spread, her victims contacted police, and there were eight formal charged filed. As more and more of her past caught up with Amelia Mildred Carr, it was only natural for police to consider her crimes were not limited to her various cons. Perhaps the Philadelphian she married in 1921 was Robert Mountford, perhaps it was some other poor soul. Perhaps there actually was no wedding in 1921. I found no follow-up to the next story, but I think it – and especially the one after that – indicate how authorities came to believe the woman was capable of anything, even murder, but nothing was ever proven. On February 25, 1942, she was found guilty and sentenced to serve eight to 12 years in prison. Prosecutor Wachenfeld, now aware of Mrs. Carr's criminal history, estimated she had fradulently obtained a million dollars during her career, but she wasn't finished. She was released from prison after eight years, and was soon arrested again. |

||

|

||

What happened after that, I do not know. I have not been able to find an obituary. Obviously, she was much more influenced by her mother's daydreaming than by her father, who for several years was a Philadelphia policeman. |

| HOME | CONTACT |

They called her

They called her