| HOME |

|

| First assignment: interview a performing chimpanzee |

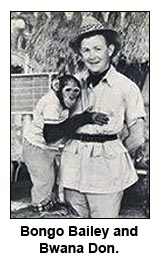

By Jack Major Most of my stories appeared in the newspaper’s television supplement and were based on interviews with performers who had visited Ohio to However, my first interview — during the first week of January, 1962 — was a humbling experience. My subjects were a performing chimpanzee, Bongo Bailey, and its owner, Don Hunt, known as Bwana Don on his Detroit TV show. Much bigger celebrities awaited, though only a few would prove more intimidating. As I recall Bongo and I had a pleasant conversation — he never lied or even exaggerated — but the story I wrote may be lost forever. ANYWAY, the girl and I broke up a few months later. She moved to California, but I stayed in Akron and kept accumulating clippings, though not in any neat and organized fashion. (I piled ‘em up on top of the scrapbook in a cardboard box.) That box went with me from Akron to Pittsburgh, then to Rhode Island in 1969. Soon I had a second box, filled with newspaper pages and stories from the Providence Journal. Both boxes, plus a few more that contained family photos and other memorabilia, were put in the basement or the attic of our home in Cranston, RI. All the while I told myself that some day I’d go through all my stuff, probably after I retired. Retirement arrived late in 2001. A few months later my wife and I moved to South Carolina so she could care for her widowed mother without flying back and forth. Like everyone who has ever moved after being in one house for more than 25 years, my wife and I – and our three children – discovered we had been saving a lot of stuff for no reason. Even after discarding enough things to fill a huge dumpster, and then some, we took approximately 150 boxes of various sizes to South Carolina, where about 20 of them remained unopened for several four years. THAT CHANGED after a visit from one of my wife’s dearest friends from high school. She and her husband asked about my newspaper experience. When I mentioned the interviews, I was very surprised to find them interested, perhaps because they were old enough to remember most of the people I had talked to. (Previously I had been asked about my job by several of our new neighbors in Bluffton, but they were in their 30s, or younger. When they asked who I had interviewed, most of the names elicited a blank look ... because there wasn't a Brad, Scarlett, Taylor or Zac among them.) Since her friend had been interested, my wife made me promise to put copies of those interviews on a disk, my computer or my website ... any place that would be safer than a cardboard box. When I finally looked at them, some of the clippings understandably crumbled at my touch. What was interesting is that one of the people I met had become much more popular in the 21st century than she was when I met her in 1963. Who would have guessed back then that Betty White's career was just warming up? My interviews would have been much better if Google had been around in the 1960s. I went into some of those interviews with practically no knowledge — first hand or otherwise — of the person on the receiving end of my questions. TIME OUT for some perspective. It was late in 1961 when the Akron Beacon Journal created its version of TV Guide. Newspapers all over the country were doing likewise. These television supplements were very popular with readers and considered important for maintaining and even increasing circulation. Yet feature sections were not highly regarded by hard-nosed reporters in the newsroom and newspapers weren't particularly choosy about folks that were hired for positions in the features department. You didn't need much experience to qualify. The first editor of the Beacon Journal's TV magazine was a college classmate of mine, an ROTC lieutenant who went on active duty at the end of the year, creating the newspaper opening that I filled, and I filled it perfectly, if I do say so myself. I had the advantage of attending nearby Kent State University and taking editing courses taught by Murray Powers, the Beacon Journal's managing editor. I also had a misspent youth, seeing many more movies than a growing boy should, which prepared me for a certain group of actors I'd seen meet — one-time film stars forced to look for work in television. It's important to recall how different things were in 1962, particularly in cities the size of Akron (population 290,000 and rapidly declining). The city had only one television channel, and it was UHF, not VHF, difficult to receive and with a tiny audience. People in Akron and throughout northeast Ohio watched television on the Cleveland channels, and reception with rabbit ear antennae was an iffy thing. Sometimes it was like seeing programs in a snowstorm. Although my title was TV editor, for several months on the job the only television I owned had a tiny screen — about six inches, I'd estimate — and even when reception was good, the picture was grainy. When actors asked if I'd seen their programs, I always said I had, but sometimes that was a lie. That all changed late in 1962 when I bought one of those humongous entertainment centers that included a large TV screen that allowed me to watch programs in living color, though several remain televised in black and white. As I recall, I received five channels, and there was no remote, so much of my exercise came from getting off the couch and walking to the TV and back. IT SOON occurred to me that one drawback of fame is being imposed upon by members the media who ask the same — often silly — questions over and over and over. As a member of the media, I admit I became tired of asking those questions. During my thirty-eight years in a features department, most of them with the Providence Journal, I met many celebrities either in person of over the telephone. Most, bless 'em, handled my questions with patience and grace, others turned the Q&A session into a game (often telling imaginative lies with a straight face), while a few simply said, "That's a stupid question!" and challenged me to smarten up in a hurry. You'll find many of my stories listed elsewhere. What follows here are things I most remember about other interviews, some of which, for various reasons, did not result in stories. But first, thanks again to Laurie Loverde, wherever she is. That scrapbook remains one of my top five favorite gifts. |

| * * * |

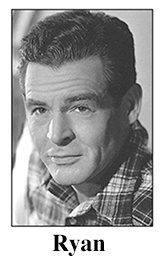

Robert Ryan was one of my favorite actors, and I was pleased to have the opportunity to meet him in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1972 while he was filming "The Man Without a Country." My wife and I had two cars — a fairly new Ford station wagon and a nine-year-old Oldsmobile that had Wouldn't you know it — Ryan (right) needed a ride from his hotel to the ship that was being used for the movie. He graciously agreed to take his chances in my junker, and refrained from making snide remarks, but it was soon apparent he had other matters on his mind. His wife, Jessica, had died recently and he was battling lung cancer that would take his life less than a year later. His career included probably the best boxing movie ever made ("The Set-Up. 1949"). He also starred in the excellent "Crossfire" (1947) and "Clash by Night (1952). two classic World War Two films, "The Longest Day (1962) and "The Dirty Dozen (1967), the memorable "Bad Day at Black Rock (1955), and three notable Westerns, "The Naked Spur" (1953). "The Proud Ones" (1956) and "The Wild Bunch," plus several other films. I would have loved to talk to Ryan about his career, but this was not the time or place. He dismissed most of the films he had made as "crap," and, no doubt, some of them were, but Ryan's standards were perhaps too higher. The man had a lot of class. I just wish I'd met him years earlier. Trivia note: He and his wife sold their Manhattan home in the Dakota to John Lennon. |

| * * * |

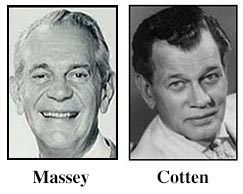

Several one-time movie stars made the transition to television in the 1960s. Like Ryan, they could have told enough interesting stories to fill a book, but their interviews with the likes of me were set up to promote a television appearance, and to do it in fifteen minutes or less, because they would be on the phone all day with many journalists. So not only did you I like to think that was the case for two interviews I had for actors who no longer were in demand for top roles in big movies. though both worked regularly on television. Raymond Massey was co-starring on "Dr. Kildare" and Joseph Cotten was guest starring on several series and narrating "Hollywood and the Stars." Massey simply didn't like my questions and obviously felt talking to me was a waste of his time. I can't remember what I asked, but I had an interest in career beginnings and the reasons people went into acting. For Massey, that was ancient history; he wanted to talk about his TV show, apparently. I should have asked him how he like working with James Dean on "East of Eden." Cotten and I might well have been doing a comedy skit. I had found articles which I thought had given me some background on the actor, but my every question had him replying, "I don't know what you're talking about; I never did that." I swear, if I had asked him about his wife, actress Patricia Medina, he would have denied even knowing her. |

| * * * |

When I vacationed in California in 1964, the Akron Beacon Journal extended my stay a week so that I could visit Los Angeles and interview several television stars, including Lola Albright, an Akron native whose career took off after she played singer Edie Hart in the hit series, "Peter Gunn." The interview took place in a restaurant owned by her husband, Bill Chadney, a pianist who was a member of the band that worked in the fictitious nightclub, Mother's, featured on the TV program. During the interview, Ms. Albright mentioned that Chadney was keeping an eye on us from behind the bar because he became jealous when he saw her talking to other men. I thought she was kidding, but she wasn't. Chadney was her third husband. They divorced in 1975. Her second husband was vastly underrated actor Jack Carson, whose talent for comedy probably got him tagged as a lightweight. But he managed to steal most of the scenes in all of his movies, including "Mildred Pierce" and "Cat on a Hot Tin Roof," though my favorite is "Roughly Speaking," with Rosalind Russell, in which Carson makes a most memorable entrance. (He seems to be wearing a chandelier as a hat. I've looked and looked, but cannot find a photo of that scene from the movie ,) In 1962, Carson performed near Akron at the Canal Fulton summer theater in a forgettable comedy called "Make a Million." Carson and his castmates were about 10 minutes into their opening night performance when two ladies arrived and began looking for their seats. Carson stopped the show, and walked over to the section where the ladies were seated. The small stage was in the center of the theater, so the performers were fairly close to everyone in the audience. He told the ladies, "You're probably wondering what has happened in the play so far . . . " And he proceeded to bring them up to date, and did it in entertaining fashion. When he reached that point where the latecomers arrived, the turned toward his castmates and resumed the production. |

| * * * |

At some point during my years in Akron, another Carson, this one named Johnny, performed one night at nearby Kent State University. A press conference was held, and I suspect the comedian and "Tonight Show" host groaned when he learned how the event would begin. The mayor of Kent happened to be named John Carson, and he had a son also named John. The press conference began with the familiar announcement, "Heeeere's Johnny," but it was the mayor who walked out, followed a minute later by his son. Finally the real Johnny Carson was introduced, and the mayor gifted him with a golf club because Carson usually swung an imaginary club e during his monologue on his TV show. Carson gave an entertaining press conference and a very funny show that evening at the Kent State gymnasium. However, he left a sour taste in my mouth when I learned that when he checked out of his motel, he left the golf club behind on the bed. I didn't expect him to treasure the gift, but he at least could have disposed of it some other way. |

| * * * |

The most entertaining interviews didn't always produce interesting stories. In March, 1966, Oscar-winning actor Gig Young ("They Shoot Horses Don't They") was the guest host of "The Mike Douglas Show." I met him after the first show of the week. With him was his fourth wife, Elaine Williams, and we went to their hotel and had jovial conversation, the kind you might have with old friends — or someone who's tipsy enough to believe you're an old friend. Young had a drinking problem and minutes after I met him, I knew the interview, as such, would be worthless. I didn't realize how troubled Young was. He and his wife divorced months later. In 1978, he married for the fifth time, to a woman named Kim Schmidt, but three weeks later, at their Manhattan apartment, Young shot and killed her, then took his own life. |

| * * * |

The longest interview I ever had was with Ozzie and Harriet Nelson, who were performing about an hour east of Akron at a summer theater in the city of Warren. The play was "The Marriage-Go-Round," which had been made into a movie a few years earlier with James Mason, Susan Hayward and Julie Newmar. (Playing the Newmar role in Warren was Sally Kellerman, then unknown.) There was one other part, and that was played by veteran actor Lyle Talbot, a long-time regular on the Nelsons' ABC-TV show where he played neighbor Joe Randolph. This was 1962, the era of celebrity-centered summer theater. There were two of them close to Akron, the one in Canal Fulton, which had a resident company that worked with a different star each week, and one an hour's drive to the east in the city of Warren. That theater was run by a producer named John Kenley, who also had a summer theater in Columbus, Ohio. (Later the Warren operation would move to Akron; Kenley would also have theaters in Dayton and Toledo.) It was a bit of a coup for Kenley to sign the Nelsons, who had seldom played anyone but themselves. They remained pretty much the same in their roles as a professor and his wife, who were forced to deal with a sexy young woman who arrived in hopes of having the professor father her baby. Anyway, at Ozzie Nelson's urging, we talked all afternoon, through dinner, and he invited me to watch the play that evening. I'd heard he was a taskmaster, not the most pleasant guy to be around while he was directing his long-running family television show, "The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet," but the man I met was like a friendly next door neighborhood. He'd rather talk about sports than show business. It was one of the most memorable days of my life — especially because of an incident that occurred in the dressing room before the show. Talbot charged into the dressing room and hid in the restroom. A minute or so later producer John Kenley appeared. Kenley, a transsexual, spent his winters in Florida living as a woman. Why he was pursuing Talbot, I don't know, because the actor was happily married and had four children. Kenley might as well have been in drag for the way he asked, "Has anyone seen Lyle?" Nelson and I said we hadn't seen Talbot, who remained away from Kenley until the show began. I was unaware of it at the time, but apparently there was a tradition at Kenley's theaters to have a cast party after the opening night performance. It was expected that the leading man would open the festivities by dancing with Kenley. |

| * * * |

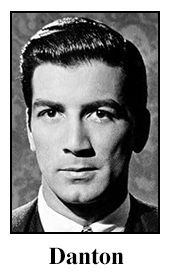

While waiting to meet an interview subject who was appearing that day on "The Mike Douglas Show," I'd be seated in a room close enough to hear what was going on behind the scenes. When Muhammad Ali, still calling himself Cassius Clay, was on the show, he wouldn't leave until he'd been paid in cash. He would not accept a check. I don't recall what the fee was in those days — guests received only $320 to appear on "The Tonight Show" — but Douglas staffers scraped up enough money to satisfy the boxer's demands. When actor Ray Danton, who specialized in playing villains, was doing a play for John Kenley at his Warren theater, he went to Cleveland to Meanwhile, Danton was furious, and after the program let the Douglas people know he did not appreciate playing second fiddle to a relatively inexperienced actor while he (Danton) had starred in such films as "Portrait of a Mobster" playing Legs Diamond and "The George Raft Story," playing the title role. He also was featured in "The Longest Day." His tantrum was memorable, and, I thought, justified. |

| * * * |

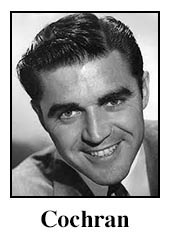

Speaking of movie villains, one of the best from the mid-1940s through the mid-'60s was Steve Cochran. He was soooo bad, some folks hissed as soon as his face appeared on screen. Cut to an evening in 1973. I'm at the Golden Lantern Restaurant in Warwick, Rhode Island, where Buster Bonoff and his lovely wife, He also was the only celebrity I ever interviewed who stared at me, then held up both hands and joined his thumbs and forefingers to create a frame for my face. "You're a dead ringer for Steve Cochran," he said, regarding this as a big compliment. Which it might have been if I had known Cochran as anything but the despicable characters he played on screen. |

| * * * |

| Thanks to the Bonoffs, my wife, Linda, and I also had dinner with Rita Moreno when she performed at Warwick Musical Theater in 1978. Ben Vereen also was there, but he arrived at the Golden Lantern Restaurant with a large dog in tow — a Borzoi, I believe — and didn't seem interested in socializing. Ms. Moreno, however, was delightful company, knowing ours was an off-the-record conversation. She had just received word of an Emmy nomination for outstanding guest actress for her role as call girl Rita Kapcovic on "The Rockford Files." She would later win the Emmy and repeat her role 20 years later in a TV movie,"The Rockford Files: If I Bleeds, It Leads." |

| * * * |

In 1972, I had a phone interview with Alan Alda, one of the few performers to make good on a promise he made about his upcoming TV series. "M*A*S*H will not be like any other sit com you've ever seen," he said. That much I remember. Unfortunately, the story that resulted from that interview did not survive the move to South Carolina. |

| * * * |

A 1964 interview with comedian Jackie Mason was had me feeling like a combination shrink and one-person focus group. Like several entertainers who co-hosted "The Mike Douglas Show," Mason arranged spent his evenings performing at a local club. "Douglas" turned out to be an easy gig; not so his night job. When I interviewed him over lunch after his second day on the TV show, he was upset by his nightclub experience the evening before. His audience was much smaller than he anticipated and less receptive. "I guess I'm not known in Cleveland," he told me. "I have a feeling that if I went up to someone here and said, 'I'm Jackie Mason,' the guy would answer, 'So what?' " He spent much of our interview trying out new material and asking my opinion. He was polishing a routine about a baby's first day in the world, and while it was funny in spots, I found myself squirming, not laughing. My reaction was tactful, not necessarily honest. Mason first attracted attention in the Borscht circuit in the Catskills. The former rabbi was a big success before a predominately Jewish audience. Steve Allen heard about him and booked him on his TV show in 1961. Ed Sullivan followed. Mason and Sullivan would have a falling out in the mid-'60s. It wasn't long after I interviewed Mason that his career went into a long slump. He bounced back big time in 1986 with a one-man show "The World According to Me." That title pretty much summed up the attitude Mason assumed during a performance where one of his signature lines was, "It's such a pleasure for you to be seeing me." Mason lent his voice to Rabbi Hyman Krustofsky for several episodes of "The Simpson." The comedian passed away on July 21, 2021. He was 93 years old. |

| * * * |

Burton "Buster" Bonoff operated the Warwick Musical Theater in Rhode Island and expected local newspapers would give good coverage to every act that was booked each summer. When faced with an unusual situation, Bonoff would come up with creative ideas to insure that coverage. Which is how, in 1972, I came to fly with Bonoff to Cleveland to visit an Ohio venue that had booked a unique show that would soon arrive in Warwick. Bonoff was curious about the show, so curious that he had to see it to believe it could actually work at a relatively small theater-in-the-round. The show's star was Olympic gold medal figure skater Peggy Fleming, who managed to create a scaled-down ice show for venues that ordinarily held music or comedy concerts. She brought along other performers — a singer and a comedian, I believe, though I can't recall who they were — but she was the main attraction, and she didn't disappoint, though it was like she were skating in a living room. What I recall most about meeting her after the show in Ohio was the contrast between Ms. Fleming's elegant, princess-like image and the down-to-earth young woman who chugged a bottle of beer while she talked to Bonoff and me. |

| * * * |

James Drury is mostly remembered as the title character in one of television's most ambitious weekly series, "The Virginian," which cranked out 90-minute episodes. It was a quality Western that ran nine seasons. What I recall most about my 1968 interview with him in Cleveland was what happened after I left him. I met him while he was on a publicity trip accompanied by a girl friend (who may have been Phyllis Mitchell, who became his second wife later that year) and his bodyguard, who was about my height (6-foot-3), but muscular and scary. I made no attempt to go drink-for-drink with Drury, who enjoyed his scotch so much that our table and his right elbow remained strangers throughout the evening. Fittingly, when Drury became very, very mellow, he slipped into a Richard Burton impression. An excellent Richard Burton impression, by the way. I was convinced that had Drury been cast in a good police or medical drama that he probably would have a different, perhaps more successful career and would have been recognized as a damn fine actor. As it was, Drury had acquired a reputation for being taciturn and frequently hostile, but he proved unusually friendly for a celebrity who was saddled with a journalist for more than three hours. It was close to midnight when I finally said goodbye, politely declining Drury's invitation for another round of drinks. Thus I missed the most exciting part of the evening. Soon after I left, Drury's bodyguard decided to try out pick-up lines on women seated at the nearby bar. Another patron, undoubtedly fueled by liquid courage, figured out the identity of the man in the horn-rimmed glasses having drinks with the best-looking woman in the place. He approached Drury, belched the old cliche ("Well, if it isn't The Virginian! I bet you think you're sooooo tough!"), then found himself face-to-face with the lightning-quick bodyguard, who'd spotted trouble, and responded by grabbing the man and hurling him through a large window, onto the sidewalk out front. Or so I was told the next day by someone at the Cleveland NBC affiliate, who may have exaggerated a bit. At least, I hope he did. |

| * * * |

It was in the fall of 1966 when Robert Loggia, then 36, starred in an NBC series with an overly cute title, "T. H. E. Cat," the initials standing for Thomas Hewitt Edward, while Cat was his last name. Tom Cat was a mysterious character, a former circus aerialist, and reformed cat burglar, now a sort of freelance bodyguard. The show test-marketed well, but when the 1966-67 season began, it was clear from the get-go "T. H. E. Cat" was in ratings trouble. Loggia, who'd played swashbuckling hero, Elfego Baca, in 10 episodes of "The Magical World of Disney," also was an effective villain in his earlier movie and TV appearances. His character in "T. H. E. Cat" was somewhere in between, and there was an effort to make the series rather dark and decidedly different, heavy on Lalo Schifrin's music and an assortment of colorful characters in offbeat settings. But the television audience wasn't buying it, and in November NBC sent Loggia on a publicity tour that included a stop in Cleveland. That's where I and a young woman reporter from a suburban daily interviewed Loggia, who announced he would not talk to us unless we had seen his program. The woman hadn't, so she was sent away. I'd only seen a few minutes of one episode, but I made it seem like I'd watched more of the show, so I was allowed to remain. Loggia was proud of the show, but was candid about its ratings problem and said changes would be made to broaden its appeal. Those changes didn't work and the series was canceled. The actor had a distinctive hoarse, gravelly voice, that seemed better suited for older characters, which may be why Loggia's career improved steadily as he aged into some interesting supporting roles. He balanced his work on television with several supporting roles in films, where he played a wide range of characters, most notably in "Big" (with Tom Hanks in 1988) and "Jagged Edge" (1985). which earned him an Oscar nomination for his performance as an investigator for the lawyer played by Glenn Close. |

| * * * |

| In 1969, I had a phone interview with Julie Sommars, a promising young actress who had made a splash in a movie comedy, "The Pad and How to Use It." But instead of pursuing a movie career, she agreed to star with Dan Dailey in a TV sitcom, "The Governor and J. J.," playing Dailey's daughter. The series lasted a season and a half, but in those days programs cranked out 26 episodes a year, or more, and if you were able to stream "The Governor and J. J.." you'd find there are 39 episodes to watch. Anyway, I'd discovered that phone interviews with celebrities started the same way. They'd ask the first question, and invariably it was, "How's the weather?" Since most of the people I interviewed by phone were in California, I figured this was their way of rubbing it in. I mean, they couldn't possibly care whether it was raining, snowing or sunny where I was. Julie Sommars was different. "This is the first time I've ever done phone interviews," she said, "and I feel sort of uneasy about it. For one thing, I'd like to know what you look like." "I'm a dead ringer for James Farentino," I lied. Well, it wasn't a complete lie, at least not to a co-worker who had noted such a resemblance a few weeks earlier. It was the first and last time anyone ever made such a comparison. "Then you must be very good looking," she said. "I made a movie with Jim, and he's a very attractive, very nice guy." Thus we touched upon a big advantage phone interviews. If I were still doing them, I'd claim to be Jon Hamm's long-lost twin. |

| * * * |

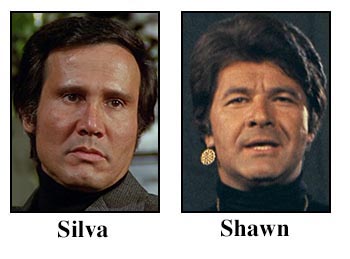

On two occasions, actors came to see me at the office to be interviewed. Henry Silva's name probably never was on the tips of many tongues, but his face is unforgettable. In 1971 when he came to Providence, on his own dime, to promote "The Animals,"in which Silva played an Apache who tracks down five men who robbed a stagecoach and raped a woman passenger. You could call it a Western version of "Death Wish," except "The Animals" came first, three years before the much more successful Charles Bronson film. For thirty years Silva made his presence felt in movies and television programs, though none of his performances matched the impact of his role as Chunjin, the Korean scout who led Frank Sinatra's Army unit into There was a hush when he walked into the newspaper office. He was taller than I expected (about six-feet-one, or seven inches higher than most actors I’ve met), but was just as cool in a light brown suit (with subtle stripes) and a quietly colorful tie. (Or, as Rex Reed might put it – the suit was butterscotch parfait, the tie was a tropical fruit salad,) But this wasn't the usual celebrity sighting. Silva was likely to give you chills, not thrills, though he proved to be a pleasant, soft-spoken man who had no illusions about himself or his career, and seemed more than satisfied with the limited success he'd gotten from his unusual looks. The other performer who dropped by the office to talk was actor-comedian Dick Shawn, who was born Richard Schulefand in Buffalo, New York, in 1923. At the time of his visit to Providence, my office at the Beacon Journal was in an abandoned radio station on the top floor of our building. I wasn't easy to find, so I had to give Shawn a lot of credit when he arrived. I'm not sure who or how many saw him during his visit; nor can I remember why he was there or what he was promoting. The story that resulted from our meeting was lost somewhere between Rhode Island and South Carolina. If Shawn's name doesn't register, then look him up. He was a force of nature — think Robin Williams — whose early stand-up television appearances were hilarious. Even in person he seemed larger-than-life. His most memorable performances were as Ethel Merman's frantic son in "It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World," and as actor LSD (Lorenzo St. Dubois in the above photo), who would be cast as Hitler in the 1967 Mel Brooks movie, "The Producers." I'm convinced that had he been properly harnessed and handled, Dick Shawn would have been one of Hollywood's biggest stars. He died April 17, 1987, after suffering a heart attack during a performance at the University of California, San Diego. |

| * * * |

It was during my only California visit in 1964 that I was invited to an Emmy Awards party where I met Irene Ryan, who'd been nominated as best actress in a comedy series. (She correctly predicted Mary Tyler Moore would win, complaining just a bit that the industry had no respect for her series, "The Beverly Hillbillies.") Ryan was surprisingly friendly and got along especially well with my traveling companion and former Kent State classmate, Lynn Kandel. She invited us to visit the set of her series, which was about to wrap up filming of its last episode of its third season. A day or two later Lynn and I visited the set, had a brief chat with Ms. Ryan, then watched her film a scene — during which she was bitten by a chimpanzee, probably the one known on "The Beverly Hillbillies" as Cousin Bessie. Such incidents were not unusual for actors working with chimpanzees, and this one required that Ryan be taken to a hospital. As she was being driven away, she told her driver to stop. She rolled down a window, called Lynn and me over, and apologized for what had happened. It was an amazing gesture. What I recalled more vividly was Buddy Ebsen's reaction to the chimp incident. He loved Irene Ryan and all that, but Ebsen was anxious to finish the season and begin his summer hiatus. Given his druthers, Ebsen probably would have strangled the animal. Ebsen and I had talked weeks earlier in a phone interview in which he expressed some complaints about working in television. “There’s no doubt about it,” Ebsen said at the time, “television is an actor killer. We work too hard and use too much material. If I could un-invent anything, it would be television. No foolin.’ But we’re stuck with television and have to make the best of it. Ever the realist, Ebsen wanted to continue working after "Hillbillies" ran its course, and to do that he soon began another series, playing a private detective in "Barnaby Jones" for seven seasons and 178 episodes. |

| * * * |

A girl that I dated once upon a time accused me of being to critical and she offered this piece of wisdom: "Loretta Young always used to say, 'Never criticize an Indian until you've worn his moccasins for two weeks. Or something." She had mangled the message, but I knew what she meant. I should keep my mouth shut until I put myself in other other person's place to understand his point of view. That was in 1964, and taking my date's advice, I attempted to wear the moccasins of Bill Dana while he was in Cleveland to promote his television program. I had to put myself in his shoes or else it would have been one of the shortest interviews on record. Even a person who wasn't normally critical could say nasty things about "The Bill Dana Show." Thus it was necessary to understand that at least one person – Dana – must think the program [about a hotel bellboy] is funny and that at least one person – Dana, again – still broke up over those four well-worn words, "My name . . . Jose Jimenez." In this agreeable frame of mind I even ordered the same meal Dana did – steak tartare, a fancy name for raw hamburger. He finished his; I quit after one bite. For me, it wasn't easy wearing Dana's moccasins. |

| * * * |

Some of my in-person meetings with female actors — formerly known as actresses — were akin to speed dating. They were short conversations, not really interviews. My 1964 California visit included a stop at Universal Studios where I met Cheryl Holdridge and Allyson Ames, who seemed more concerned with personal matters than their careers. We chatted in a recording studio where they were dubbing lines for an episode of "Wagon Train." Holdridge was a former Mousketeer who'd recently celebrated her 20th birthday. She was preoccupied with her romance with Lance Reventlow, son of Woolworth heiress Barbara Hutton. Reventlow had recently divorced actress Jill St. John, a sore subject with Holdridge, who correctly predicted on the day we met that St. John no longer was in the picture; she and Reventlow would wed. Which they did six months later. Reventlow, also a pilot, would be killed in 1972 in the crash of a small plane. Holdridge would marry twice after that. She died in 2009. Ames was considered a better actress than Ms. Holdridge, but her career came to an end soon after she she married producer-director Leslie Stevens, who worked on such TV hits as "Outer Limits," "The Name of the Game," "McCloud" and "The Virginian." Their marriage lasted about one year. In 1964, Ames was a single mother with two or three children. During our conversation she joked that if I wanted an interesting look at the glamorous life of a young actress I should stop by her apartment for dinner, which I took to be a reference to caring for and feeding her children. Holdridge egged me on, as though Ames were asking me out, but I figured I was being drawn into a joke, the punchline of which would be "Gotcha!" Both women had work to do, so I excused myself and left. I had lunch with Barbara Anderson in 1967 at a restaurant in Brecksville, Ohio. She was single, not yet 22 years old, and had come out of nowhere to be chosen to play Officer Eve Whitfield on the Raymond Burr series, "Ironside," which also featured Don Galloway and Don Mitchell. I don't recall much of the interview except that she was pleasant, forthcoming, and not at all affected by her sudden success. However, because her success was so sudden, she didn't have any amusing or interesting anecdotes to share about her work or her co-stars. She went on to win an Emmy as outstanding supporting actress in a drama series in 1968 and was nominated for the award the next two seasons. In 1971 she married former actor-turned-stockbroker Don Burnett, 15 years her senior and once married to actress Gia Scala. Barbara Anderson left "Ironside" after the 1970-71 season, and worked sporadically after that. Unlike a lot of TV critics, I thoroughly enjoyed "Dallas," and when a publicist offered an interview with Deborah Shelton, I immediately said yes. Who's Deborah Shelton, you ask. She's a former Miss USA and runner up in the Miss Universe Pageant. But "Dallas" fans remember her as Mandy Winger, J. R. Ewing's sexiest and most interesting mistress. Unknown to me until the interview started was that that Mandy Winger had been written out of “Dallas.” Instead, Shelton wanted to talk about her movie career, but the more she talked, the more I was certain her film career would go nowhere. Her first post-"Dallas" film was a German comedy — that's right, a German comedy — called "Zartiche Chaoten II," which translated as "Lovable Zanies II." (Her co-stars included Michael Winslow, Thomas Gottschalk and the ever-popular David Hasselhoff.) In any event, my interview with her didn't produce anything interesting enough to put into a story. She wouldn't be drawn into juicy gossip about "Dallas," and I couldn't get interested in "Lovable Zanies II." In 1976, Raquel Welch, her film career apparently not headed in the right direction, made what I thought was a gutsy move — she went on tour as a singer. Among her stops was the Warwick (RI) Musical Theater. As it turned out, I thought she performed surprisingly well, and after the show, Burton "Buster" Bonoff, with a gleam in his eye, asked if I wanted to meet the glamorous woman who had starred in such films as "Myra Breckenridge," "Hannie Caulder," and "Kansas City Bomber," and had held her own with some biggies in Richard Lester's "The Three Musketeers" and its sequel. Bonoff popped into her dressing room, and she told him she had a few minutes to talk to the fellow who had just reviewed her show. She was very gracious, though obviously in no mood to be interviewed. We talked for a few minutes, but when I suggested maybe she'd rather be alone, she smiled and said, "If you wouldn't mind." Thus ended my "date" with Playboy's choice as "the most desired woman" of the 1970s. |

| * * * |

I also met a candidate for "the most desired woman of the 1980s," but I met her in 1965 when she was a rather shy and quiet 22 years old. That's when Linda Evans was featured in the Barbara Stanwyck Western series, "The Big Valley." ABC sent Evans on a publicity tour, and I saw her in Cleveland during an uneventful group interview. The show hadn't yet aired and Evans was a virtual unknown, though she had made several guest appearances on television, including five appearances on "The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet." Years later, a much different Linda Evans emerged. The woman who became a big, big star in "Dynasty" was like the steroids version of the actress who'd played Ms. Stanwyck's daughter. For that we could thank her long relationship with John Derek, who'd also married Ursula Andress and Bo Derek. On television, the bionic woman was Lindsay Wagner; in real life, she was Linda Evans. |

| * * * |

Like Jack Carson, Van Johnson was a vastly underrated movie star from back in the day. Perhaps Johnson was dismissed as the song and dance man he was on Broadway before his first break in Hollywood. However, after surviving a disfiguring automobile accident in 1943 as he was about to star with Spencer Tracy in "A Guy Named Joe," Johnson was taken more seriously. MGM wanted to replace him in the movie, but Tracy insisted production stop until Johnson had recovered. A few facial scars may have changed his appearance slightly, and hardened his image somewhat, but it they did not hinder his career. He When the dinner theater craze hit in the 1970s, Johnson was ripe for roles in several plays and musicals. I don't remember which one brought him to the Chateau de Ville in Warwick, Rhode Island, but it did get me a luncheon interview at a small French restaurant in Providence. He made a star's entrance and was upbeat and almost too cheerful throughout lunch, but he kept to the subject, which was to promote his show. The result was a pleasant lunch, but a routine interview. I've read that in his private life, Johnson was often morose. He'd been married during his early years in Hollywood, reportedly to mask the fact he was gay. I'd have loved to have interviewed him at length about his movie career, but there was no reason Johnson would ever have given me that much time. It wasn't until these interviews were no longer part of the job that I had the opportunity to watch and enjoy at my leisure several of the folks I had either met in person or talked to over the phone. I wish I had do-overs with Raymond Massey and Joseph Cotten, because DVDs and streaming allowed me to have a better appreciation of their careers, though I was far less impressed by Cotten than I was by Massey. But my biggest surprises were Van Johnson and especially Jack Carson, whose presence brightened so many movies. |

| HOME | CONTACT |

appear on “The Mike Douglas Show,” which at the time originated from Cleveland, or those who had phoned me from California to plug a television series.

appear on “The Mike Douglas Show,” which at the time originated from Cleveland, or those who had phoned me from California to plug a television series. 93,000 miles on it when I bought it. The Olds also had a leak in the windshield, resulting in a musty odor inside. The front seat was torn, the engine was loud, and the exhaust left a trail of smoke.

93,000 miles on it when I bought it. The Olds also had a leak in the windshield, resulting in a musty odor inside. The front seat was torn, the engine was loud, and the exhaust left a trail of smoke. not have much time, but the person on the other end of the phone might be a bit frazzled if you were his or her tenth call of the day.

not have much time, but the person on the other end of the phone might be a bit frazzled if you were his or her tenth call of the day. promote the show and found his on-air time greatly reduced because Douglas extended his interview with Paul Petersen, a teenage regular on "The Donna Reed Show." It was summer and Douglas felt Petersen appealed to teens who might be watching because they were on vacation. And apparently the studio audience enjoyed the young performer, who had launched a short-lived singing career.

promote the show and found his on-air time greatly reduced because Douglas extended his interview with Paul Petersen, a teenage regular on "The Donna Reed Show." It was summer and Douglas felt Petersen appealed to teens who might be watching because they were on vacation. And apparently the studio audience enjoyed the young performer, who had launched a short-lived singing career. Barbara, invited me to join them and Don Rickles, who was performing at Bonoff's Warwick Musical Theater that week. Rickles, famous for his cruel jokes at the expense of famous people, was, in person, one of the nicest guys I ever met.

Barbara, invited me to join them and Don Rickles, who was performing at Bonoff's Warwick Musical Theater that week. Rickles, famous for his cruel jokes at the expense of famous people, was, in person, one of the nicest guys I ever met. an ambush in the 1962 version of "The Manchurian Candidate," then later turned up in New York City as a houseboy for the brainwashed ex-GI played by Laurence Harvey.

an ambush in the 1962 version of "The Manchurian Candidate," then later turned up in New York City as a houseboy for the brainwashed ex-GI played by Laurence Harvey. went on to deliver memorable performances in a wide variety of roles. He was at home in musicals, comedies and dramas. I thought he was particularly good in two World War Two films, "Battleground" and "The Caine Mutiny," and later was hilarious as a swinging car dealer (left) in the Dick Van Dyke-Debbie Reynolds film, "Divorce American Style."

went on to deliver memorable performances in a wide variety of roles. He was at home in musicals, comedies and dramas. I thought he was particularly good in two World War Two films, "Battleground" and "The Caine Mutiny," and later was hilarious as a swinging car dealer (left) in the Dick Van Dyke-Debbie Reynolds film, "Divorce American Style."