Part 14:

After Cassie Chadwick's death, she was mentioned frequently in the press, usually whenever a female forger or con artist was arrested. I was surprised how often this happened, and it took only a few minutes to come up with the following examples. There probably are many more I could have found had I spent an hour or two looking.

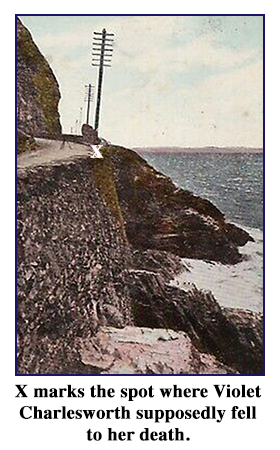

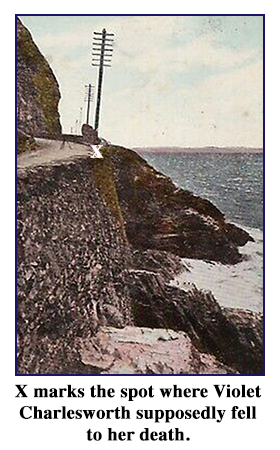

Pictured above is perhaps the most interesting con woman to grab headlines in the wake of Cassie Chadwick's case. She's Violet May Charlesworth, often called "The Cassie Chadwick of England." Her career ended when she was just 25 years old, and while she seemed surprisingly savvy about business affairs, she succeeded mostly on youthful good looks, a winning smile, and an unwillingness to take "no" for an answer.

More later on Ms. Charlesworth and the other con women of the early 20th century. First, a look at two postscripts to the Chadwick case: |

Washington Evening Star, August 28, 1908

CLEVELAND, Ohio, August 28 — The writing of the last official chapter in the records of the monumental swindles of the late Mrs. Cassie Chadwick was begun yesterday when her husband, Dr. Leroy S. Chadwick, filed a petition of bankruptcy in the United States district court here. With assets of $75, except for medical books and office fixtures valued at $1,700, which he claims to be exempt, Dr. Chadwick hopes to wipe out obligations aggregating over $600,000.

The action of Dr. Chadwick is considered to be only formal in effect, for the purpose of clearing himself from any connection with the various notes his wife gave and which he had indorsed. Although Dr. Chadwick was jointly indicted upon one of the transactions with his wife, yet he never was brought to trial and the case was nolled. Mrs. Chadwick died in the Ohio penitentiary a few months ago.

Dr. Chadwick originally had a fortune of upward of $50,000. This soon was wiped out by the debts of Cassie Chadwick, as was a considerable portion of the estate of some of his relatives. It was this fortune and the good name the Chadwick family bore here which formed the basis of his wife’s later manipulations and machinations.

|

|

| By the time the next item was published, Dr. Chadwick had joined his daughter and his brother, Bingham, in Jacksonville, Florida. |

Chicago Daily Tribune, January 15, 1910

CLEVELAND, Ohio, January 14 — The Euclid avenue mansion of the late Cassie Chadwick, “financier,” is being wrecked to make room for a synagogue, to be the finest in the city.

|

|

| I wonder what was more painful to the doctor — his family home being torn down or the fact it was now referred to as Cassie Chadwick's mansion. Dr. Chadwick died in Jacksonville in 1924. He was 71 years old. His daughter, Mary Isabel Chadwick, also remained in Florida, and married Ion Nalle. She died in 1960 in Jacksonville at the age of 74. Her husband died two years later. |

| * * * |

Other con women used Cassie's game plan

It was a reference to Cassie Chadwick in a 1921 story about con woman Amelia Everts Carr, also known as "Petticoat Ponzi," that lured me into a search for more information about the woman whose birth name was Elizabeth Bigley. However, whenever she's remembered, it will be as Cassie Chadwick, with whom other con women were compared for many years. For example:

• "Much Like Mrs. Chadwick Was a Hohokus, N. J. Woman" was the headline in the Chicago Daily Tribune (December 26, 1904) for a story about Mrs. Juliette C. Henderson, who posed as the heir to a big estate, borrowed money in large sums, and spent it lavishly. She died leaving assets valued at $15,000 and owing $200,000.

• "Her methods are said to have outrivaled Cassie Chadwick's," said a story in Genoa (NY) Tribune (July 27, 1906). Mrs. Helen Hulshizer of Joliet, Illinois, was called “The Woman Plunger,” and it was said she, like Lydia Devere, hypnotized men and woman “of the utmost financial ability and social standing” out of thousands of dollars. Her exploits appear to be exaggerated. I found only one other story about her, from 1909 in the Chicago Daily Tribune. She was a fugitive at that point, and apparently successful at hiding. The Genoa Tribune story said she ha a daughter, Edna Thayer, who was an actress.

• Police are looking for Chan Chow Yut, “a veritable Chinese ‘Cassie Chadwick’,” said the San Francisco Call (November 28, 1907). The woman swindled the Los Angeles Chinese Women’s Deposit Syndicate out of $30,000, and was thought to be headed for Salt Lake City.

• A headline in the Waterbury (CT) Evening Democrat (February 15, 1908) called Mrs. Mary E. Cochrane a rival of Cassie Chadwick, probably because Mrs. Cochrane wrote letters of introduction and forged signatures of prominent people to dupe Francis T. F. Lovejoy, former partner of Andrew Carnegie, who gave a $100,000 mortgage on his Pittsburgh mansion to Mrs. Cochrane and received $1 in return.

• "Oneonta Produces a Cassie Chadwick" declared the Broadalbin (NY) Herald (July 19, 1908); The woman was a 50-year-old spinster named Caroline Andrews, who disappeared owing people in her town $20,000. She was described as one of the hardest workers at the Oneonta Baptist Church, president of the Ladies’ Aid Society and WCTU, and treasurer of the Woman’s Club. She borrowed most of the money she owes from friends, including one woman who mortaged her home to raise $7,500. She also was into a sister-in-law for $3,500.

• "May Be Second Cassie Chadwick" was how the Wilmington (DE) Evening Journal (July 21, 1908) introduced readers to Miss Frances A. Casnari, formerly of Baltimore, arrested for passing worthless checks. She'd already spent time in Maryland penitentiary.

• According to the Wausau (WI) Pilot (November 30, 1909) the "Cassie Chadwick of Wisconsin" was Mrs. Mary Mohr, sentenced to seven years in the Iowa peniteniary for defrauding a woman of $250 and 100 pounds of honey. Previously, she conned people in Wausau. Said a Wisconsin victims, "She could charm the money out of one’s pocket." He added, "It was the wonder of everyone how she did it, because she was homely as a Kentucky rail fence, and spoke a language that needed fixing.”

• A headline over a photo in the Los Angeles Herald (April 6, 1910) said, "Local 'Cassie Chadwick' Being Carried from Jail.” The story began: "Screaming at the top of her voice and kicking in an endeavor to free herself, Mrs. Ketturia M. Osborne, who gaine a reputation as 'Cassie Chadwick the Second,' was carried from the women’s department of the county jail yesterday afternoon and taken to the Southern Pacific Station, where she left for San Quentin to serve a sentence of five years." She specialized in real estate fraud, such as selling non-existent houses.

• The Albany Argus (November 19, 1916) referred to Miss Annie Sharpley as "a second Cassie Chadwick" after she borrowed $81,000 from several people “on no other security than her personality and ingenuousness.” She promptly lost the money in various business ventures and went into hiding with only five dollars to her name.

• Mrs. Myrtle Bowman Hayes was called “Modern Cassie Chadwick” by the Albany Knickerbocker Press (May 13, 1923). This was a fairly sensational case because Mrs. Hayes had forged the name of Charles M. Schwab to the tune of $325,000.

|

| * * * |

And now, here's Violet!

Somewhere in the middle of all the above was Violet May Charlesworth, who was so appealing she may have lived happily ever after if she hadn't made enemies of Mrs. Martha Smith and Dr. Edward Hughes Jones, whose combined contributions to Miss Charlesworth's fortune were relatively small. She very easily could have repaid Mrs. Smith, and she shouldn't have promised Dr. Jones she would marry him. Meanwhile, several men who had given her the means to acquire jewels, homes and automobiles were content to sing, "Thanks For the Memories."

But before telling you more about Miss Charlesworth, a synopsis of The Humbert Affair, the French scandal that broke in 1902, two years before Cassie Chadwick was arrested. Because Mrs. Chadwick was American and Thérèse Humbert was French, United States newspapers tended to make a bigger deal out of the Clevelander's crime, when, in fact, the Humbert case was far more spectacular. So while American newspapers compared Violet Charlesworth with Cassie Chadwick, in Europe she was more likely to be called "The Second Thérèse Humbert." |

New York Tribune, December 13, 1904

Thérèse Humbert d'Aurignac was the daughter of a poor French farmer. When a young woman, she married Frederic Humbert, whose father was a prominent public man of Paris.

For a term of years Mme. Humbert carried on a gigantic swindle at the French capital. She obtained loans on the basis of alleged securities supposed to be in a safe and duly sealed, representing a fortune of $24,000,000. This fortune she declared was left to her by Robert Crawford, a wealthy American, whom she and her sister aided and nursed to health in an illness.

The story she told was that Crawford's relatives were seeking to deprive her of the money, and the securities could not be taken from the safe until the litigation was ended.

On the alleged securities, the sum of $145,000,000 was procured by loans or renewals in a period of twenty years, of which Mme. Humbert and her husband are believed to have used $10,000,000. They lived in fine style, had a luxurious home, fine paintings, costly plate, expensive equipages, and moved in the best circles of Parisian society, some of the leading men of the city being among their victims.

When exposure finally came, the Humberts fled to Madrid, but were taken back to Paris, and after trial in 1903 were sentenced each to five years' solitary confinement in prison. |

|

For more about the Humberts, the quickest way is to click on The Great Expectations of Therese Humbert. On the surface, she and Violet Charlesworth seemed to have little in common, except a lower middle-class upbringing, a desire for easy living and a lot of nerve, and Miss Charlesworth did something Mrs. Humbert couldn't — she used her good looks to charm her victims, and struck it rich a lot earlier in her life. While Mrs. Humbert's partner was her husband, Miss Charlesworth had a lot of help from her mother, who launched the con by spreading the word her daughter, whom she had named May, stood to inherit a fortune from the estate of the girl's godfather, Major-General Charles "Chinese" Gordon, a British hero who'd been killed in the Sudan in 1885, a year after May was born. (Charlton Heston played Gordon in the 1966 movie, "Khartoum.")

It was May's idea to call herself "Violet Gordon," which led to variations of her name — Violet May Gordon, Violet Charlesworth Gordon, even Violet May Gordon Charlesworth. Her mother probably had no idea of the problem she created for her daughter when she said the inheritance would be hers on her 25th birthday — January 13, 1909 — because that created a deadline for the scam, a deadline that would prove inconvenient, prompting Violet Charlesworth to make a fatal mistake. |

| * * * |

In Derby, she's off and running

May Charlesworth grew up in Stafford, England, in an area of the country called the West Midlands. Her father was a mechanic, her mother was a dreamer and a schemer who originally came up with the idea for the scam that would make her daughter famous. This is how it was explained in "Sin and Scandal in Edwardian Britain: Fraudster Heiress Violet Charlesworth," by Evangeline Holland: |

Violet’s life of crime began in 1900, when her mother set the ball rolling by informing a Dr. Barratt that Violet and her eldest daughter were to inherit a fortune of £75,000 upon the eldest daughter turning twenty-one. This daughter died before twenty-one, but two years later, Violet, now eighteen, claimed a young man named Alexander McDonald promised to settle £150,000 on her when she reached the age of twenty-five. On the strength of this so-called legacy, Violet’s mother was lent various sums by a Mrs. Smith from 1903 on.

Noticing how easily duped people were by these huge lies, the Charlesworths undoubtedly figured they could aim much higher. In 1907, the Charlesworths decamped to Rhyl, a seaside resort in Wales, where they spread the news that Violet was god-daughter of General “Chinese” Gordon of Khartoum and was to inherit £100,000 from his estate upon her twenty-fifth birthday. |

|

This Mrs. Smith was the widow who eventually would file criminal charges against the mother and daughter. It was money from Mrs. Smith's life savings that launched Violet Charlesworth on the most interesting part of her operation — speculating on the stock market.

A few years later, after Miss Charlesworth's scheme had been exposed, it was explained that the Panic of 1907 in the United States led to her downfall: |

New York Times, March 6, 1910

One stock broker declared Miss Charlesworth owed his firm $50,000 for speculation, mostly in American railroads. She had first written to his firm in 1905, saying she would like to speculate in a small way. At first she made considerable money. Then came the American panic, and she failed to cover her deficit. They had pressed for payment and finally had an interview with Miss Charlesworth in a London hotel.

“We were expecting,” said the stock broker, “to see a middle-aged woman of the world, but found a country girl, quietly dressed in the best taste and with a charming manner. She told us she had a fortune coming to her when she became 25 in January, 1909. She would not tell us who her trustees were, and had kept it a secret from them that she was operating on ‘Change. She promised me $250 on account, which she afterward paid, and $500 as a guarantee against unsuccessful operations. When she was pressed, she induced us to advance $2,000 on her jewelry, which was extremely valuable.

“She gave us to understand that her fortune would amount to $2,500,000. She told us her trustees were purchasing estates in Scotland and Wiltshire. Finlly her bills with us amounted to $50,000. She emphatically declared they would be paid as soon as she came into her fortune.”

Then, added the stockbroker, a soft expression came into his stolid countenance: “Her eyes were of a curious reddish tinge, and were her strangest feature. She could talk in a marvelous way — talk anyone around to her view.” |

|

Time for some clarification. I have no idea if the New York Times article adjusted figures to account for the difference between the American dollar and the English pound. In 1910, when this article appeared, the reason for using a dollar sign may have been as simple as the symbol for pounds (£) wasn't available on the newspaper's linotype machine. Dollars or pounds, 2,500,000 was a huge amount in 1910, and that's what Violet Charlesworth was claiming would be coming her way on her 25th birthday.

As the above article indicated, her early speculation paid off. Here's what another newspaper wrote (and you'll notice it has the symbols for both dollars and pounds): |

New York Press, January 18, 1909

Luck was with her for a long time, and with her winnings she began to live on a more elaborate scale. That enabled her to get more credit. She bought a magnificent estate near the old home of her parents and turned it over to them. Then she bought a country home near London, and finally she purchased an estate in Scotland ... She [has] admitted she spent £40,000 in the last year.

Jewelers were glad to give credit to the young woman and automobile manufacturers didn’t question her when she ordered her cars. Five months ago she bought a new machine for $7,000.

|

|

| * * * |

Enter Dr. Jones

Coming to Violet Charlesworth's temporary rescue when her stocks tumbled in 1907 was Dr. Edward Hughes Jones. In some ways, they reminded me of Cassie and Dr. Leroy Chadwick. Their relationship was driven by money, not love, but would lead to a lawsuit instead of a wedding. I had to be impressed with the way she convinced the doctor she really had a connection with the Gordon clan: |

"Flower Shows, Fraudsters & Horrible Murders: The Secret Journal of Aaron Allott, 1887-1950"

In 1907 Violet was suffering from some illness, and Dr. Jones was called in to attend her. Soon afterwards Dr. Jones received a letter from a London firm of solicitors, Messrs. James and James, thanking him for the care he had taken with her, and later received two scarf-pins from a Mr. Robert Gordon, through the firm of solicitors, one for himself and one for his brother, who was in partnership with him. These, it was inferred, were chosen by Miss Charlesworth herself

|

|

Believing the charming young woman was an heiress, Dr. Jones proposed. She accepted, and soon after they became engaged, he lent her £100, believing it was a safe investment. She soon asked for more ... and more.

After she had "borrowed" £5,000 from her fiance, Violet took a house in Wiltshire at a rental of £180 per week, and used it for her St. Bernard dogs; and a few weeks afterwards rented a house in Scotland at £250 per week.

When he testified against her in 1910, Dr. Jones said Miss Charlesworth put off their wedding with a story about a Colonel Williamson, who was handling the Gordon trust that would be hers on her 25th birthday. She said Colonel Williamson wanted her for himself and would make sure she didn't receive her money unless she broke her engagement to Dr. Jones.

Meanwhile, her bills mounted while her stocks tanked, and she kept creditors at bay by assuring them they would be paid soon after she turned 25 on January 13, 1909. But as that birthday approached, Violet Charlesworth plotted a way to avoid admitting to the world that she was a fraud.

|

| * * * |

Ooops! Bad idea

She was living in a large, rented house in St. Asaph, Wales, near the seacoast town of Rhyl, when she and her sister, Eileen, and a chauffer named Albert Watts went on an automobile trip along the coast, with Violet driving. About 9:30 p.m. they reached Penmaenmawr, several miles west of Rhyl, when ... |

New York Sun, January 31, 1909

... she ran her motor car through a gap in a wall running along the cliffs on the coast of North Wales. She then threw her cap and an empty notebook over the cliff, walked to a neighboring station and took a train to Scotland. Her sister and the chauffeur were left on the road to be discovered by the first passerby and tell the story of the fatal accident. This they did with a wealth of unnconvincing detail.

Miss Violet Gordon Charlesworth, the owner of the car, was driving,, the chauffeur was sitting beside her, and her sister was behind, they said. The car turned suddenly, crashed through the wall, and Miss Charlesworth was thrown from behind the steering wheel clear through the wind screen and over the cliff. The chauffeur and the sister jumped out and lay stunned for some time.

|

|

Police knew from the get-go the story was a phony. There was no sign of the body on the rocks below, and the car showed no signs of damage and was driven away the next day. Violet had selected a poor spot for her accidental death. It was shown to be impossible for a body to reach the water from that spot. Also, the water below, even at high tide, is only 18 inches deep, but when the accident occurred, the tide was ebbing. Police knew from the get-go the story was a phony. There was no sign of the body on the rocks below, and the car showed no signs of damage and was driven away the next day. Violet had selected a poor spot for her accidental death. It was shown to be impossible for a body to reach the water from that spot. Also, the water below, even at high tide, is only 18 inches deep, but when the accident occurred, the tide was ebbing.

Violet Charlesworth obviously was still alive, and the search was on. Everyone was on the lookout for a young woman known for wearing a red cloak which had become her trademark. |

Chicago Sunday Tribune, February 21, 1909

A London reporter hit a trail which eventually cleared up the tangle. Miss Violet had always been an enthusiast over Scotland and things Scotch. She had adoped a Scotch name and history and had loved to dress herself as a bonnie Highlad lassie and bemoan the unhappy fate of the romantic house of Stuart. The reporter decided Scotland would be the place she would most likely hide, and he picked up a decided clue in a small north north of England town where he found a scarlet-cloaked woman had stopped for a day in order to have the telltale garment dyed. The scene grew hotter and hotter and finally landed him in the Scottish resort town of Oban.

At a hotel he discovered Miss Violet or her double. The woman declared her name was Margaret Cameron McLeod, and with the umost indignation disclaimed any knowledge or connetion with the mising Charlesworth. She even went so far as to write a letter to the London papers complaining that she was being persecuted; she threatened to put the matter in the hands of her lawyers if she suffered any further molestation.

It was a good bluff, but it failed to work.

|

|

Violet Charlesworth owed £60,000, but her assets totaled only £10,000. Some creditors had hopes of being repaid at least some of their debt when the young woman was offered work in vaudeville, but hers wasn't muchh  of an act. All she had to do was walk around the stage in her red cloak while an announcer recited the story of her adventures. of an act. All she had to do was walk around the stage in her red cloak while an announcer recited the story of her adventures.

A brief review in Variety (February 20, 1909) said she "was hissed and not treated any too well" by audiences, adding, "Violet isn't so much on looks." I thought that last remark was rather harsh because photographic evidence indicates she was rather attractive, but more cute than gorgeous. One photo, in particular, had me thinking the late Joan Hackett would have been perfect in the role of Violet Charlesworth.

While her first few shows packed 'em in, the novelty of Violet Charlesworth was over in a week, but it was several months before she faced the consequences of her scam, and only because of two complaints.

In March, 1910, Violet and her mother were convicted of fraud in the matters of Mrs. Martha Smith and Dr. Edward Hughes Jones, though the defense got the doctor to admit he probably wouldn't have proposed to Miss Charlesworth if he hadn't believed she was an heiress. Mother and daughter were sentenced to three years at hard labor.

Violet Charlesworth was released from Aylesbury prison on February 10, 1912, her sentence punishment shortened as a reward for good behavior. When her mother was released, I do not know, but both of them faded into obscurity.

To me, the weirdes part of the Violet Charlesworth tale is that when Major-General Charles "Chinese" Gordon, a bachelor, was killed in 1885, he left an estate worth only £2,315. You'd think the people who loaned money to a woman in the early 1900s would have known that, or, at least, done some checking. |

| * * * |

|

Cassie Chadwick lives on

In addition to being compared with every female con artist and forger for many years, Cassie Chadwick's name surfaced from time to time for other reasons. |

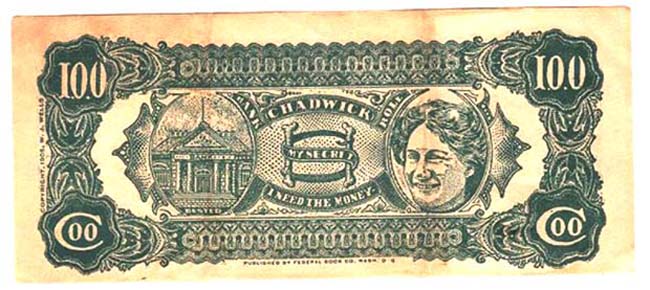

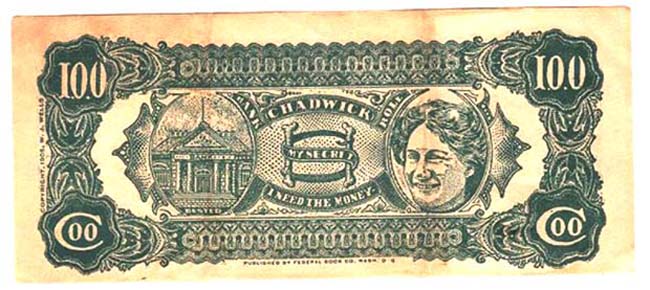

Washington Evening Star, August 7, 1908

Chief John Wilkie of the Secret Service is arranging to call upon District Attorney Baker of this city to suppress a local enterprise — the printing of what is called “Cassie Chadwick money.”

The Federal Book Company of this city prints the money and sells it to stores dealing in novelties. It is noticed in display windows throughout the city and is often flashed by humorously inclined persons wishing to give the impression of great wealth.

The Cassie Chadwick currency bears a likeness of the celebrated easy money adventuress, as well as a photograph of a “busted” bank. Two years ago when it was designed, a sample was submitted to Assistant Secretary Keep of the Treasury.

After consultation with Chief Wilkie and with the United States attorney of the District, the inventors of the paper were informed that, while the novelty has a good many points resembling a $100 bill of the United States, it was technically not a violation of the laws, declaring that nothing shall be printed in similitude of an obligation of the United States goverment.

Immediately the supposed money came into great demand, being sold freely to visitors in the city. For some time no complaints were received of any improper use of the fake money, but in the last few months three complaints have come from different parts of the country, stating it has been passed off for real money.

Four or five days ago, Jerry Larkin was arrested at Clayton, N. Y., for passing one of the novelties for $100. He must stand trial on the charge.

Secret Service officials state that while the Chadwick bill does not bear sufficient resemblance to a $100 bill to deeive native citizens, it can be used to impose upon nearly arrived foreighners. They consider it is assuming serious importance for that reason.

One side of the Chadwick currency is printed in yellow, in imitation of a large government note. In each of the upper corners are the letters I. O. U., but the U is so nearly like the figurre naught that is is calculated to deceive.

The majority of the United States attorneys have refused to permit the Chadwick currency to circulate in their jurisdictions.

|

|

|

Then there was this tidbit about a dancer who performed under the name "La Petite Adelaide."

She was born Mary Adelaide Dickey in 1882 in Cohoes, New York, and had a long and successful career on stage as both a solo performer and as half of a duo with Johnny J. Hughes, whom she later married.

In 1910 she must have been making a lot of money, and she spent a chunk of it on one of Cassie Chadwick's trinkets. |

|

New York Press, July 21, 1910

A $20,000 dog collar of pearls and diamonds which formerly belonged to Cassie Chadwick was purchased yesterday by La Petite Adelaide, the dancer who is appearing in "The Barnyard Romeo" on the American Roof Garden and in "Up and Down Broadway" in the Casino Theater.

When she appeared last night she wore the collar for the first time, and it attracted much attention. It is the purpose of La Petite Adelaide to wear the string of gems hereafter at all her performances.

When Cassie Chadwick was engaged in high finance schemes she left most of her jewelry, valued at many thousands of dollars, with the Citizen's National Bank of Cleveland, Ohio, as collateral for loans. After she was sent to prison, the bank sold the gems in a lot to a New York jewelry firm. In the lot was the dog collar, containing 225 pearls weight five-and-one-half grains each, arranged in five strands, divided by four bars of filigree work ornamented wth 140 diamonds. The diamonds in the filigree work weigh in the aggregate ten carats.

|

|

| |

|

| References: |

Newspaper articles found on fultonhistory.com

1. "Lawsuits and Bank Failure Follow Suit Against Woman," Associated Press, Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, November 29, 1904

2. "Carnegie Starts An Inquiry," New York Globe and Commercial Advertiser, December 2, 1904

3. "Mrs. Chadwick Has Promise," New York Sun, December 2, 1904

4. "Chadwick Notes Worth $5,000,000," Chicago Sunday Tribune, December 4, 1904

5. "Mrs Chadwill in Cell in Tombs," New York Herald, December 9, 1904

6. $5,000,000 Bundle Open, Worthless," Chicago Daily Tribune, December 10, 1904

7. "Carnegie Death Key to Audacious Chadwick Plot?," Chicago Sunday Tribune, December 11, 1904

8. "The Great Chadwick Drama," Philadelphia Inquirer, December 11, 1904

9. "High Old Doings in Chadwick's Euclid Ave. Mansion at Cleveland," Buffalo Courier, December 12, 1904

10. "Mrs. Chawick's Statement Called Untrue by Lawyers," New York Herald, December 15, 1904

11. "Carrie Chadwick, Hoodwinker of Bankers," by Cora Rigby, New York Herald, May 2, 1915

12. "The Strange Case of Mrs. Chadwick," Collier's, December 31, 1904

13. "Girl Who Upset England, New York Sun, January 31, 1909

14. "The Last Phase of the Charlesworth Case," New York Times, March 6, 1910

15. "Carrie Chadwick, Hoodwinker of Bankers," by Cora Rigby, New York Herald, May 2, 1915

16. Cassie Chadwick Took 'Em All to the Cleaners, Edward J. Mowery, Long Island Star-Journal, April 4, 1962

Articles online:

18. "The Fabulous Fraud from Eastwood," by Willis Thornton, Maclean's Magazne, November 1, 1949

19. "Cleveland: The Best Kept Secret," Chapter XII: "Cassie Was a Lady," by George Condon, Doubleday, 1967

20. "The Woman Who Robbed Oberlin College (Among Others)," Milena Evtimova, The Oberlin Review, November 10, 2006

21. "The High Priestess of Fraudulent Finance," Karen Abbott, Smithsonian Magazine, June 27, 2012

22. "Cassie Chadwick: World Famous Con Artist," Owlcation, December 20, 2020

23. "Nerves of Steal: Cassie Chadwick, 'Patron Saint of Confidence Woman'," Brian Benoit, April 5, 2021

24. "Cassie Chadwick: The Female Wizard of Finance," Quincy Balius, Ohio History Connection, June 22, 2022

25. "Queen of Sham," Paul Roberts, Woodstock Newsgroup

26. Cassie Chadwick, Encyclopedia of Cleveland History

27. "Cassie Chadwick: The Con Artist of Millionaires' Row," Western Reserve Historical Society

28. "Sin and Scandal in Edwardian Britain: Fraudster Heiress Violet Charlesworth," by Evangeline Holland

29. The Great Expectations of Therese Humbert, strangeco.blogspot.com

30. An Invisible Crown: How to Be an Heiress, Izabella Scott, June 16, 2020, affidavit.art

31. Flower Shows, Fraudsters & Horrible Murders: The Secret Journal of Aaron Allott, 1887-1950 |

| fultonhistory.com is a free website which encourages donations (though don't expect a receipt or even an acknowledgement). It's not the easiest website to negotiate — few are these days — but there are millions of newspaper pages available, most of them from old New York publications, msny of which no longe exisr. With a little patience, you'll be amply rewarded. |

| |

|

Police knew from the get-go the story was a phony. There was no sign of the body on the rocks below, and the car showed no signs of damage and was driven away the next day. Violet had selected a poor spot for her accidental death. It was shown to be impossible for a body to reach the water from that spot. Also, the water below, even at high tide, is only 18 inches deep, but when the accident occurred, the tide was ebbing.

Police knew from the get-go the story was a phony. There was no sign of the body on the rocks below, and the car showed no signs of damage and was driven away the next day. Violet had selected a poor spot for her accidental death. It was shown to be impossible for a body to reach the water from that spot. Also, the water below, even at high tide, is only 18 inches deep, but when the accident occurred, the tide was ebbing. of an act. All she had to do was walk around the stage in her red cloak while an announcer recited the story of her adventures.

of an act. All she had to do was walk around the stage in her red cloak while an announcer recited the story of her adventures.